The New Naked

Your eyes will never be normal. Dr Mark Terry, Surgeon, Devers Eye Institute, (explaining why post-surgery I still can’t see well enough to read or drive or cross the road safely without corrective lenses).

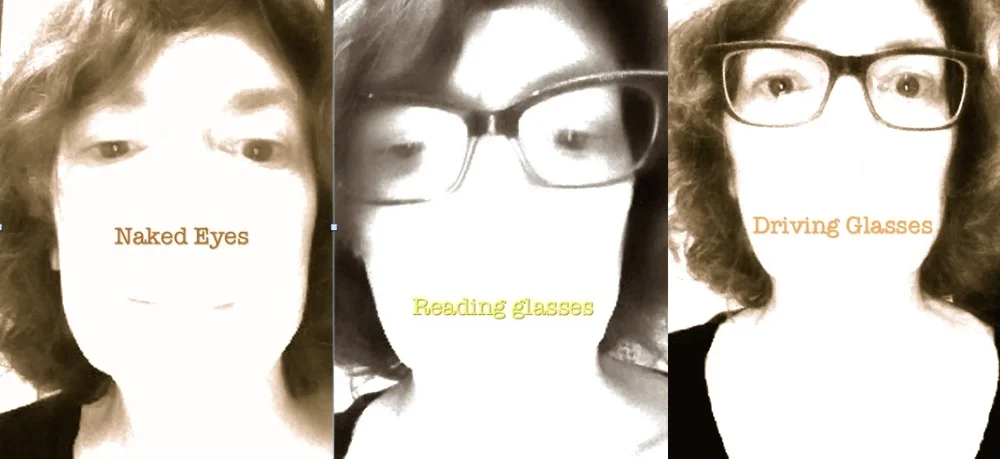

I never thought to call it naked before. It was just how I saw. Or, to be more precise, how I didn’t see, until I put my contacts in. I didn’t spend a lot of time there.

Recently, two high power intraocular lenses have been surgically implanted through small corneal incisions. (And from the twilight zone of anesthesia, I could see the scalpel). Although these lenses correct a good portion of my myopia, they aren’t quite bionic enough to take me all the way to what’s considered normal sight. The technology isn’t there yet. The new lenses bring my naked vision to about 20-200—the official number for legal blindness.

It’s a good starting point—and compared to before, not the least bit blind. It’s vision that offers me choice.

My naked vision is soft. It erases the eye puffs and chin hairs, smoothes out flaws in the skin (thank you). At first it bothered me that I didn’t notice a tear drop forming in the corner of my client’s eye. But then I saw it with my ears, like in my dream years ago, when the message came—your ears will be your eyes. Or did I feel his lone tear? What are these senses anyway? How do they work?

My naked eyes are blurry like my old ones, but way more user-friendly. I can function. Like my original eyes but on steroids.

Add to this a pair of reasonably fashionable glasses. Voila. Sharp vision for reading and computer work. No more shoulders to ears, and neck to the front. No more squinting. What’s close up, what’s in front of my nose has become obvious. This is good, I guess. It makes me a more reliable dishwasher and reduces the cost of chiropractic and massage care. Not sure yet what it does to my sensing.

Next, a pair of hip and attractive distance glasses offers me a realistic idea about what’s up ahead on the road. Realistic can be very useful (if not life-saving) in the real world—for instance while driving or riding my bike. Said glasses allow me to distinguish maple leaves from sycamore, horses from cows in the farmer’s field and crows from hawks in the sky (which may or may not help with my life-long animal nomenclature issues). I have learned that clouds are not all puffs —some have very distinctive shapes with edges—falling stars do actually appear to streak down the sky, and the man in the moon could just as well be a woman.

Yesterday was a first. While out on my bike, I spotted (and I was the one to point it out, despite my riding in the rear!) a nimble lightly colored deer prancing through the pasture way up ahead, about to cross the road—into oncoming traffic. The thrill of seeing was instantly tempered by my terror for the creature’s life, and there was nothing I could do. Thankfully, we all survived the shock.

All this clear seeing, and these multiple choices are weird. Really weird.

Jerry keeps imploring me to use a different word. Can’t you think of something more descriptive?”

And I can’t. Not. Yet.

They say there is an adjustment period of 6 – 12 weeks while the brain slowly adapts, and learns to see again. In my case it means seeing the sharp edges of the real world for the first time.

And that’s a lot to take in.